|

Find interviews by: | ||

Sherlock Holmes Director: Rachel Lee Goldenberg Jump to Part 2 of the review

Which is why it’s a shame that the only quote they could come up with was “in an extraordinary league of its own” (credited to ‘blockbuster.co.uk’) which has the unfortunate effect of suggesting this film is similar in some way to notorious 2003 turkey The League of Extraordinarily Bad Special Effects. Trust me, it’s not. It’s everything that The League of Excruciatingly Poor Acting tried to be and failed. This is, for one thing, entertaining, which the bigger film certainly wasn’t and, despite its tiny budget, this has better effects and better production values all round than The League of Exceptionally Bad Scripts. It also helps that Caernarfon looks a lot more like 19th century London than Prague could ever manage. And that the Asylum’s film doesn’t star past-his-sell-by-date old twat Sean Connery. But I’m damning with feint praise here. Almost anything would be better than The League of Explain to Me Again Why I’m Watching This Shit (you can tell I really don’t like it!). Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes - to use the eventual full on-screen title - is a belter, easily one of the Asylum’s best. The title is an oddity worth noting as the production was shot under the working title Sherlock. The trailer calls it Sherlock Holmes but the DVD and titles call it Sir Arthur... (with the possessive credit in much smaller type, of course) although it’s just called Sherlock Holmes again at the end of the credits. The dilemma, of course, was to cruise as much as possible on the back of the near-simultaneous Guy Ritchie Sherlock Holmes without making people think this was a film they had already seen. So this is kind of a mockbuster but only in the sense that War of the Worlds was, not in the more literal and obvious sense of Transmorphers or Snakes on a Train. Though not adapted - even loosely - from any Conan Doyle story, the script by Paul Bales includes a few nods to ‘the canon’. The characterisations of Holmes and Watson are pretty spot-on and while the plot itself is (let’s be honest) bonkers nonsense, the fantastical steampunk setting gives this hugely likeable film a degree of leeway which it might not be able to afford if it had a more conventional story. For a low-low-budget feature (about $150,000, give or take, from what I can piece together) this looks mightily impressive and does a great job of recreating Victorian London - which is why the one or two anachronisms and Americanisms which do creep in jar annoyingly. For example, the credits play over CG cityscapes of 19th London, one of which is a railway station. But the engine briefly seen in front of the station is very, very obviously an American railroad engine.

On the one hand, this is nitpicking: it’s on-screen for no more than a few seconds as part of a larger image and has no involvement with the story. But it gave me the thirst for a neologism: Nometgir. A Nometgir is something which is wrong but of which it can be said that it would be ‘No more expensive to get it right.’ There are a couple of other shots of a (real) steam engine in action later on which were presumably shot at the Welsh Highland Railway, which has a terminus at Caernarfon. While I’m nitpicking, the film starts with a prologue of an old Dr Watson (played by David Shackleton: Another Night, Secret Rage) in 1940, specifically 29th December 1940 which was, of course, the height of the Blitz. It’s a cheap-but-effective shot of squadrons of planes flying over London, explosions erupting below. But it is missing four things, all of which were in action throughout every single night of the Blitz: anti-aircraft fire, barrage balloons, searchlights and an ARP warden yelling “Put that bloody light out!” at the aged doctor who sits on the top floor of a building, attended by a young woman and gazing out through a lit window. Rachael Evelyn (John Carter of Mars, Ironclad) is credited as ‘Miss Lucy Hudson’, a nice touch which implies that she is the (great-?) grand-daughter of the original housekeeper. Watson comments that it is the second time he has watched London burn - and somebody has really done their homework here because 29th December 1940 was not just the biggest raid on London up to that point, it was also the night that the Luftwaffe dropped far more incendiary bombs than ever before because they knew that there was a neap tide that night, meaning the River Thames was unusually low and it would be considerably more difficult for the London Fire Brigade to reach it with their hoses. Even without showing a light, the top floor of a building is a bleeding dangerous place to be during an air raid. But Dr Watson takes this opportunity to recount to Miss Hudson an undocumented Sherlock Holmes adventure, which she dutifully transcribes. This nice little scene is let down a little in the logic stakes by Miss Hudson’s initial enquiry, after Dr Watson explains the set-up: “Who is ‘he’?” Well, ‘he’ is the bloke I wrote all those famous stories about who lodged with your Gran for most of his adult life. I’m surprised that neither I nor your Gran ever mentioned him before...

This is all well and good, and ties in with the lack here of the celebrity which is often seen to surround Holmes in later stories, as well as nice little touches like a suggestion that Holmes, though a smoker, is not yet a drug addict. But, that said, the plot hinges on Holmes and Lestrade having worked alongside each other on numerous occasions and Lestrade has a quite unsubtle and obvious dislike of Watson (which is never explained, as far as I can tell). Certainly H and W seem like old pals, not newly minted friends. Ah yes, the relationship between Sherlock Holmes and Dr John Watson. On the commentary, writer Bales calls this a “Victorian bromance” and there is a definite - but gloriously subtle - homoerotic subtext here. There are just enough moments where Holmes and Watson hold eye contact that little bit longer than two pals normally would. It’s super! There is no doubt that the casting of Gareth David-Lloyd adds to the subtext because, despite his Victorian garb and his trim moustache, he still seems like Ianto. Or at least, his relationship with Holmes smacks of Ianto and Captain Jack. Like Captain Jack, Holmes is mercurial, enigmatic, super-confident, dynamic, occasionally flamboyant and roguishly handsome. Like Ianto Jones, Dr Watson is stiffly formal, reserved, responsible and very, very loyal. It is impossible not to map the one relationship onto the other. So here’s what I’m trying to figure out: am I reading too much subtext into this because of the casting of Gareth David-Lloyd, or did they cast Gareth David-Lloyd (at least in part) in order to add a deliberate subtext? Anyway, we haven’t met Holmes and (young) Watson yet because first we have a scene on board a ship in the middle of the English Channel. We later learn that this was carrying tax money back from the West Indies which is a little odd because you would expect a ship like that to go to a West Coast port like LIverpool or Bristol. But that’s the least of the crew’s problems. It’s night-time and all seems well until someone screams that there is something in the water heading straight for them. There is much staring and peering but curiously no-one does what you or I would do in such a situation, which is change course. The whatever-it-is then disappears and all seems well until - tentacles! Yes, it’s a giant octopus. In point of fact, it’s probably the same CGI giant octopus that was in Mega-Shark vs Giant Octopus. It drags sailors off the deck, pulls down masts and generally wrecks the ship.

Lestrade (William Huw, who was Tom in Merlin and the War of Dragons) has called in Holmes to investigate the disappearance of the ship, since there was no storm and no obvious cause of its sinking. There is a single survivor, who is in hospital and quite mad, which is why Holmes has called in Watson. Somewhere around here, the plot starts to unravel, which is a shame as the film has barely started. But hold on for the ride because it’s great fun, if defiantly loopy. Holmes, Watson and Lestrade go to a cliff top, accompanied by a local rock-climber (played by a local rock-climber) with the intention of abseiling down to examine the shipwreck. Yes, we have already established that the ship sank in mid-Channel, but let’s just roll with it because there is a smashing dialogue exchange here:

David-Lloyd’s restrained exasperation makes this a gem of a moment. And there are a few others scattered around the script. Much to his concern, and entirely devoid of safety equipment except the rope tied around his waste, Watson descends the cliff. Filmed on South Stacks, Anglesey, there is some nice editing here as we repeatedly cut between a stunt double halfway down a real cliff and close-ups of the actor on a much smaller cliff. If the latter is not quite as vertical as the former, no worries. Halfway down the cliff, Watson reports that there is no sign of the ship. He does however see someone in the water who seems to be struggling but, after Watson shouts down and receives no response, turns out to be merely a wave-tossed corpse. Watson then re-ascends, surviving the predictable last-moment rope-snap, and completely fails to mention the corpse, while neither Holmes nor Lestrade seems at all bothered at the absence of the ship’s remains (an absence which is not surprising as it sank several miles out to sea). Basically, what we have here is a scene which is great in terms of character development, but adds precisely nothing to the narrative. Watson is prepared to climb down the cliff for his friend, even though it is plainly stupidly dangerous. Holmes presents a studied insouciance, more bothered about his pipe than his rope-suspended pal, but he has presumably made a careful assessment of the situation and deduced that Watson will be safe - then leaps into action when the rope frays. Meanwhile, Lestrade is determinedly indifferent and stand-offish. In character terms, this is cracking stuff.

On the DVD commentary is the revelation that this scene was not in Paul Bales’ screenplay but was added by director Rachel Lee Goldenberg to replace one in which Holmes and Watson use a Victorian submarine to examine the wreck, while fending off sharks. (There are indeed sharks in the English channel, but not many. Presumably this would have been a smaller version of the CGI shark from Mega-Shark vs...) The sub scene was deemed too difficult and expensive, even for the ambitious Asylum (you’ll see how ambitious later) which is a shame. Not just because a sequence with a submarine and a shark would have been terrific, but because I can’t help feeling that there might have been something in what they found down on the wreck which would inform the whole plot and allow it to make sense. Or maybe not. This may also explain why the cliff scene is so painfully long: they had to replace a complicated scene with the same number of pages. Holmes and Watson are separated so there’s no opportunity for dialogue and, while David-Lloyd’s acting here is top-notch, there’s only so many times you can look at Watson’s terrified stare or a close-up of his foot knocking pebbles down the cliff. It may be that the scene seems to drag because nothing happens. But my belief is that it drags and nothing happens. A somewhat picaresque narrative proceeds from here, with progression between scenes usually determined by Holmes’ ability to identify any fragment of stuff as having only possible originated in one location. First, we cut to the East End, represented surprisingly well by the streets of Caernarfon. Why this works - and this may be deliberate but I suspect it’s just serendipitous - is because in Victorian times, not everything was Victorian. It’s a common mistake, in the production design of historical films, to set everything in period. But look around you: not everything in 2010 (or whenever you’re reading this) dates from this year. Good Lord, I’m typing this on an antique desk in a 19th century house. Even my filing cabinet dates from the last century (1998 to be precise). So the fact that this cinematic East End seems to be a mishmash of Victorian architecture and older is actually just right. Not quite as old, however, as the small Tyrannosaurus rex which attacks a young man as he is attempting to negotiate a business deal with a tart. It’s a very small T rex, obviously a juvenile (well, not really, but all will be revealed later). Again from the ‘Director‘s Commentary’ (which also features associate producer/writer Bales and line producer Stephen Fiske) we learn that this was written as an iguanodon but was changed to a T rex because The Asylum already own a CG T rex and didn’t have the budget to spring for a different species. This is interesting because of course T rex was unknown to science until the early 20th century while iguanodon, as one of the first dinosaurs properly studied and described, was well known by the 1880s.

By 1882, it had finally just been established that iguanodon was bipedal, which left me thinking how brilliant it would be if some mad Victorian inventor had created a robot based on the utterly wrong quadropedal iguanodon statue at Crystal Palace, the one with the spiky thumb bone placed on its nose like a rhino horn. It had also been well established by then that iguanodon was a herbivore so quite how or why it would have savaged innocent East End kerb-crawlers is, I fear, moot. What had certainly not been established - because it was only proven about a century later - is that bipedal dinosaurs carried their bodies horizontally with their tail held out straight for balance. As late as the 1970s, models and drawings of T rex and other bipeds showed them as tripeds: bodies held upright, tail supporting them like a kangaroo at rest as they lumbered across the prehistoric plains. It’s really only since Jurassic Park and Walking with Dinosaurs in the 1990s that the public perception of theropod dinos has changed to something analogous to a kangaroo in motion (only, obviously, without the hopping) so that the tail balances the body as the creature moves at high speed. But to be fair, the fact that the inventor of this robotic juvenile T rex has correctly predicted its stance 100 years before the palaeological establishment doesn’t really matter. It doesn’t matter because it’s less astounding than that the inventor has predicted any kind of T rex twenty years before the first Tyrannosaur skeleton was even chipped out of a rock. The next morning, Watson reads about this event in the newspaper over breakfast, dismissing the report as pure sensationalism. A description of the creature, presumably supplied by the terrified moxy who witnessed the attack, says it had glowing eyes and sulphurous breath. Yet, despite this understandable exaggeration, Watson subsequently refers to it as a dinosaur - a deductive leap of appropriately Sherlockian proportions (unless he has read ahead in the script). But at this point, and running the risk of seeming like I’m doing nothing but complain about a film that I really enjoyed enormously, I must mention the worst scene in the film. It’s just a short, establishing shot of Baker Street, the camera following a young boy delivering newspapers (we actually get it twice in the film) and it has three utterly egregious mistakes, each of which is a Nometgir: no more expensive to get it right. Actually it’s four mistakes if we include the fact that young Tomos Jones has had his name unfortunately anglicised to Thomas in the end credits.

No no no, a thousand times no! No British paper boy has ever done anything like that. Not in 1882, not in 1982, not now - and if newspapers still exist seven decades hence, they won’t do it in 2082 either. It’s one Americanism which has not seeped into British society despite its ubiquity in US movies and TV. Unlike teenage proms and trick or treating and other ghastly imports, throwing newspapers will never catch on here for the simple reason that, if any British paper boy did this, every customer would complain and he would be out of a part-time job before you could say “Where’s my bloody Daily Mirror?” In the UK, newspapers are kept flat: either unfolded (tabloids) or folded once (broadsheets). A stack of them is then slid into the paper boy’s bag. No rolling, no string. You couldn’t roll most Saturday or Sunday papers anyway - they’re too stuffed full of supplements. And it would really screw up the free DVDs (although that’s not quite so germane in a Victorian setting obviously). Then - and pay attention, Hollywood - the paper boy walks up to each front door, carefully folds the newspaper and pushes it through the letterbox. So that the householder, coming downstairs, can simply pick up the paper off the doormat. I’m really puzzled that nobody thought to mention this at the time. There were only about nine or ten Americans on the production: everyone else was Welsh or English. Didn’t anyone say to the director: you know, this isn’t how newspapers are delivered in Britain. And it would have cost no more to get it right, in fact it would have been cheaper because the production budget wouldn’t have had to shell out for bits of string! But even this is overshadowed by a mistake which will, I suspect, have many Holmes purists frothing at the mouth. They have got the man’s address wrong. If there is one thing that everyone knows about Sherlock Holmes, it’s his address. He lives at 221B Baker Street. But not this Sherlock, oh no. The number on his front door is 221. And yet and yet, maybe not all Holmes purists will get apoplectic at this because, astoundingly, the Wikipedia entry on 221B Baker Street (which has presumably been written by obsessive Conan Doyle nerds) makes the same mistake, or at least the mistake which I infer from this as the best explanation for the wrong door number. I can only assume it stems from an American misunderstanding of how British addresses work.

If the building was numbered 221 and divided into discrete flats, Holmes’ address would be ‘Flat B, 221 Baker Street, London’. Note that the subdivision of the building is listed before the building itself, which is the opposite to the American way of forming addresses. In the USA, the address would be ‘221 Baker Street, Apartment B, New York’. If you will allow me a little divulgence from the actual review (you may recall, I’m supposedly reviewing a film here), this raises the interesting topic of the differences between American and British house numbering. And it’s not unreasonable that Americans should find our system confusing because nobody in Britain understands theirs. A check of Wikipedia reveals that there are umpteen different numbering systems in the States but they are mostly based on geographical location, whereas UK house numbering is purely about relative position. Most American cities have been built from scratch within the past 150 years or so, usually on a grid system which creates blocks. Sequentially numbered streets run in one direction and sequentially numbered avenues run perpendicular to them. As I understand it, the house number generally indicates how many yards the property is from the junction with the adjacent side-road. So 1234, 56th Street would be 12 yards from the junction with 34th Avenue. Or 34 yards from the junction with 12th Avenue. Or something. I don’t bloody know! The point is that the numbers are not sequential. They’re in ascending order (I think) but they don’t naturally follow on and consequently, if it becomes necessary to add a new property onto a block, this can be done without worrying about other addresses. Because the address simply denotes a specific point on the ground, irrespective of what properties might be on either side. British house numbering, on the other hand, is sequential. So when we read that, for example, Michael Jackson was born at 2300 Jackson Street, the reaction in the UK is to think, “Crikey! That’s a long street - it’s got 2,300 houses on it.” In this country, our towns and cities haven’t been planned. They mostly started as Iron Age settlements, long before anyone had even found America, not even the Vikings. And over the ensuing 1,000+ years, these towns have expanded organically, chaotically, with odd roads built around odd clusters of buildings, then new odd buildings built alongside the odd roads when the old buildings fall/burn down. There’s no grid system and none of our thoroughfares are numbered.

Sometimes, new houses will be added partway along the street, either because previously empty land is being built on or because a large building has been pulled down and replaced with two or more smaller ones. Because the British system is about relative position on the street, not geographical location, new numbers have to be inserted into a sequence which is already complete. And the way we get round this is - we stick letters on the end. So, in a nutshell, the address ‘221B Baker Street’ indicates that Mrs Hudson’s house is two doors along from 221 Baker Street, but before you get to 223 Baker Street. Her neighbour on one side is number 221A and on the other is 223 (or, conceivably, 221C). It’s nothing to do with apartments at all. Sherlock Holmes does not live in an apartment. (Of course, the address was fictional when the stories were written as Baker Street only had about a hundred houses at that time.) And that is why the sight of a Victorian lad in a white, long-sleeved T-shirt, flinging rolled-up newspapers onto the doorstep of a house at 221 Baker Street rankles so much with me. None of those things would have cost any more to get right. Gah! (By the way, if any wiki-geeks want to correct the entry on 221B Baker Street and use this as a reference, feel free.) Continue to Part 2 of the review | ||

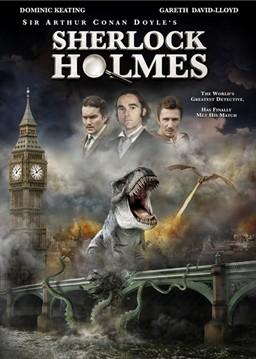

The UK sleeve of the latest Asylum feature is magnificent: dinosaurs! dragons! the Palace of Westminster alight! a giant octopus attacking Westminster Bridge! some sort of robot-thing! Sherlock Holmes himself! and Ianto off

The UK sleeve of the latest Asylum feature is magnificent: dinosaurs! dragons! the Palace of Westminster alight! a giant octopus attacking Westminster Bridge! some sort of robot-thing! Sherlock Holmes himself! and Ianto off  This isn’t something that you have to be a bit of a geek to spot (like the CG ‘American’ submarines in

This isn’t something that you have to be a bit of a geek to spot (like the CG ‘American’ submarines in  And so we flashback to another very specific date: 19th May 1882. According to various Sherlock Holmes chronologies (which I have just googled) this would make the events of the Asylum’s movie the first case solved by Holmes after his first meeting with Watson in Chapter 1 of

And so we flashback to another very specific date: 19th May 1882. According to various Sherlock Holmes chronologies (which I have just googled) this would make the events of the Asylum’s movie the first case solved by Holmes after his first meeting with Watson in Chapter 1 of  When we finally meet Watson, he is performing an autopsy. Holmes breezes in and proceeds to identify the cause of death from tiny, almost imperceptible, apparently meaningless clues - as is his wont. It’s a nice establishing scene. Curiously, there’s no precise date on it although it must be a day or two later. In fact, we never get any more date or location captions.

When we finally meet Watson, he is performing an autopsy. Holmes breezes in and proceeds to identify the cause of death from tiny, almost imperceptible, apparently meaningless clues - as is his wont. It’s a nice establishing scene. Curiously, there’s no precise date on it although it must be a day or two later. In fact, we never get any more date or location captions. But the scene drags on and on before eventually going nowhere at all. There’s all this preamble about looking at the ship but the ship’s not there and no-one cares. A dead body is there, which may or may not have some connection with the sinking, but that doesn’t even get mentioned. At the end of the scene, none of the characters know any more than they did at the start, and nor do the audiences. Narrative progression is precisely zero.

But the scene drags on and on before eventually going nowhere at all. There’s all this preamble about looking at the ship but the ship’s not there and no-one cares. A dead body is there, which may or may not have some connection with the sinking, but that doesn’t even get mentioned. At the end of the scene, none of the characters know any more than they did at the start, and nor do the audiences. Narrative progression is precisely zero. Look, I’m going to stick in a spoiler here, because it’s essential for proper discussion. A dinosaur in Victorian London has to be either the result of some form of time travel or a robot. This one’s a robot. If there was time travel afoot, a T rex would have made sense, even before its scientific discovery. But someone built this dinosaur. Presumably they built it at half-size so that it could get down narrow East End passageways and through doors.

Look, I’m going to stick in a spoiler here, because it’s essential for proper discussion. A dinosaur in Victorian London has to be either the result of some form of time travel or a robot. This one’s a robot. If there was time travel afoot, a T rex would have made sense, even before its scientific discovery. But someone built this dinosaur. Presumably they built it at half-size so that it could get down narrow East End passageways and through doors. First there’s the costume. Underneath his waistcoat, the paper boy is wearing a close-fitting, round-neck, long-sleeved top which is utterly anachronistic in terms of both style and cleanliness. This is a Victorian urchin for God’s sake - smear some crap on him. Worse than that though is the way that he is delivering the papers. He’s doing it in the American manner. That is, each paper is tightly rolled and tied with string and he is nonchalantly flinging them onto doorsteps as he walks down the street.

First there’s the costume. Underneath his waistcoat, the paper boy is wearing a close-fitting, round-neck, long-sleeved top which is utterly anachronistic in terms of both style and cleanliness. This is a Victorian urchin for God’s sake - smear some crap on him. Worse than that though is the way that he is delivering the papers. He’s doing it in the American manner. That is, each paper is tightly rolled and tied with string and he is nonchalantly flinging them onto doorsteps as he walks down the street. Here is what Wikipedia says: “The number followed by a letter is a separate number in law and indicated an apartment on the 1st floor (US - 2nd floor) of a residential lodging house that was likely to have formed part of a Georgian terrace.” This is simply wrong. For starters, Sherlock Holmes does not live in an ‘apartment’ (what we could call a flat over here). He ‘takes rooms’ in a boarding house belonging to Mrs Hudson. And as such, he does not have a separate address. If you came and stayed in my back bedroom for a while, you wouldn’t have a different address to me. 221B is the number of the whole house, not the bedroom and sitting room on the first floor where Holmes spends his time.

Here is what Wikipedia says: “The number followed by a letter is a separate number in law and indicated an apartment on the 1st floor (US - 2nd floor) of a residential lodging house that was likely to have formed part of a Georgian terrace.” This is simply wrong. For starters, Sherlock Holmes does not live in an ‘apartment’ (what we could call a flat over here). He ‘takes rooms’ in a boarding house belonging to Mrs Hudson. And as such, he does not have a separate address. If you came and stayed in my back bedroom for a while, you wouldn’t have a different address to me. 221B is the number of the whole house, not the bedroom and sitting room on the first floor where Holmes spends his time. A British street (or avenue or road or way or close or lane or...) starts with house number 1. Next door is house number 3, then house number 5 and so on. On the other side of the street, opposite number 1, is house number 2, then number 4 and so on. Odd numbers up one side, even numbers up the other. If one side has large buildings and the other small, or there’s a major interruption such as a park, then it is possible for the two sides to be completely out of sync with, say, house number 120 opposite house number 75. Where the two sides are roughly in sync despite the presence of a park or other interruption, that usually indicates that houses existed there once but have been pulled down. British streets can be quite long: my old address was number 405 and I think the road went up to about 600. But it would be extremely unusual to have a four-figure house number.

A British street (or avenue or road or way or close or lane or...) starts with house number 1. Next door is house number 3, then house number 5 and so on. On the other side of the street, opposite number 1, is house number 2, then number 4 and so on. Odd numbers up one side, even numbers up the other. If one side has large buildings and the other small, or there’s a major interruption such as a park, then it is possible for the two sides to be completely out of sync with, say, house number 120 opposite house number 75. Where the two sides are roughly in sync despite the presence of a park or other interruption, that usually indicates that houses existed there once but have been pulled down. British streets can be quite long: my old address was number 405 and I think the road went up to about 600. But it would be extremely unusual to have a four-figure house number.